No matter what shape or form it ended up taking, Taylor Swift’s newest non-“Taylor’s Version” album was destined to live in the shadow of her monumental Eras Tour. Love or hate her (or, dare I say, fall somewhere in between?), Swift firmly established herself as the biggest pop star in the world through a global victory lap asserting the strength of her discography thus far. The continued impossibility of getting tickets to the remaining Eras Tour dates only further cemented the idea that Taylor Swift as we know her is a historic phenomenon. As someone who only ended up able to experience the concert film version of the tour, I cannot think of another time when I saw moviegoers taking flash-on selfies in the middle of a movie, as if documenting oneself watching this already documented piece of media was both worthwhile for the individual and a reasonable justification for breaching the basic etiquette of going to a theater. “Sure, let the toddlers scream and run around in their princess outfits up by the movie screen, recording everything on mommy’s iPhone with the flashlight spinning around as they scramble in excitement. It’s Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour. When else will they experience this?” (The answer: two months later, when the extended cut launched on video-on-demand.)

The unspoken issue of Swift’s superstardom, though, was its paradoxical nature. Somehow, it seemed simultaneously impossible to imagine how things could get better or worse for Swift. How do you top the highest-grossing tour of all time? How do you fall from grace when your peak is this high? The latter situation seemed far more likely to happen, but no one cared to question if, when, or how that would occur. After all, the Eras tour was scheduled to continue through December 2024. Surely that problem was for future Taylor Swift to contend with.

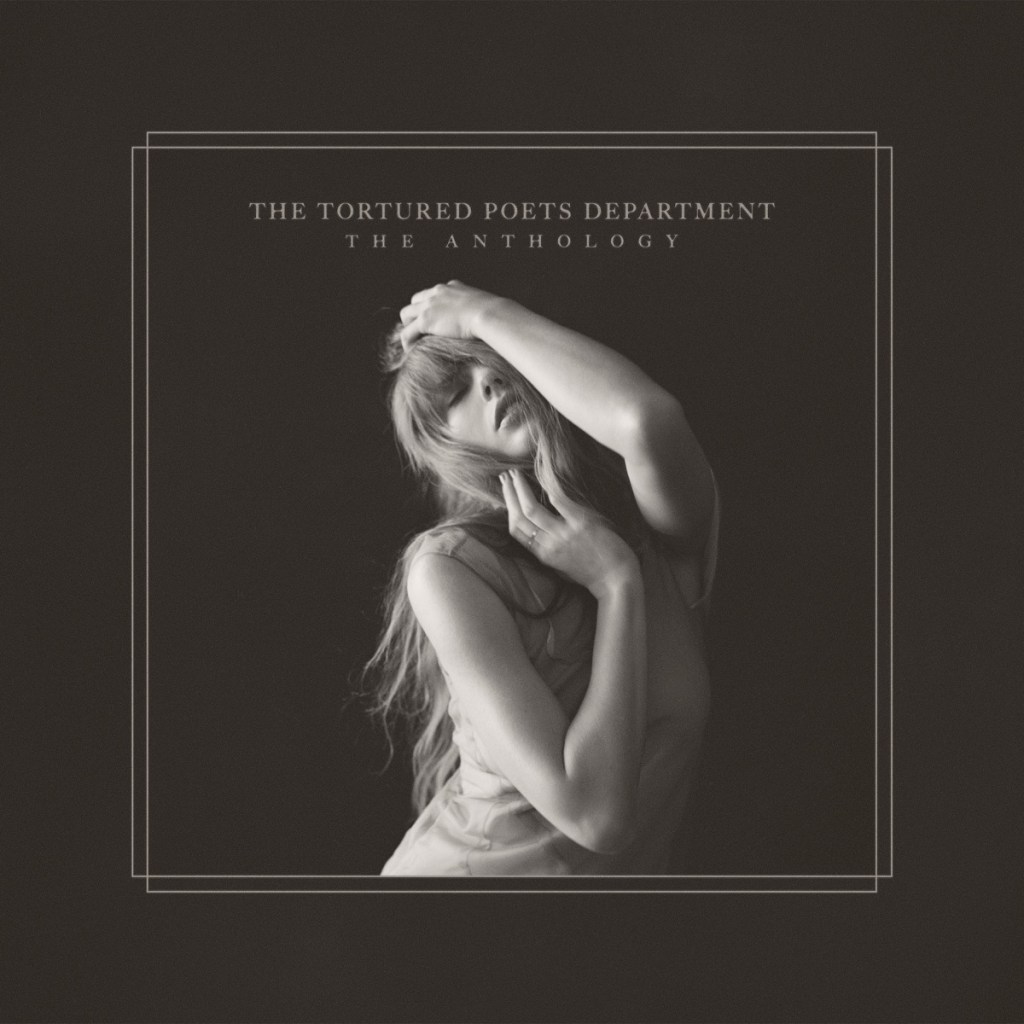

Appropriately enough, Swift’s Achilles heel arrived in the form of the unexpected: rather than announcing her highly anticipated re-recording of 2017’s Reputation, she revealed that a brand new album would arrive first. Setting aside the subjective social faux pas of announcing her album in the middle of the 2024 Grammy Awards (come on, are we really going to keep acting like the Grammys have retained any sense of prestige that outweighs their myopic, self-congratulatory nature?), something was demonstrably off about The Tortured Poets Department as soon as further details were made available. First, the title, which has been endlessly misnamed due to its uncomfortable similarity to Dead Poets Society (even The New York Times had to revise their review for referring to it as The Tortured Poets Society). Never mind that, though, as the Swifties quickly clarified that the title was an homage to the group chat her ex-boyfriend was in. But then there were the song titles and the album artwork. Cropped from the eyes up, Swift is portrayed in grayscale, writhing in an empty, snow-white bed in a position that could equally be interpreted as “erotic” or “bedrotting.” Song titles like “My Boy Only Breaks His Favorite Toys,” “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?,” and “I Can Fix Him (No Really I Can)” only reinforced the melodramatic tone Swift was clearly going for, all couched in that cumbersome album title. Then, to put the nail in the coffin, the album turned out to be a double album, with 15 songs mostly produced by folklore muse Aaron Dessner announced and released just two hours after the album hit streaming services. Clearly this was no throwaway venture for Swift, having invested an amount of music into the whole Tortured Poets Department project that nearly equaled the length of her re-recording of Red. Altogether, these factors prompted the question: how seriously is Taylor Swift taking herself on this album?

The Tortured Poets Department itself responds in kind with inconsistency and indecision. While Swift plays to her strengths in select moments, like the “so obvious of a concept it turns out to be genius” heartbreak of “loml,” too many of the double album’s staggering 31 songs aim for a garrulous pastiche of early Lana Del Rey records, warts and all. The opening track, “Fortnight,” wastes no time in presenting these surface level attempts at edginess, with Swift flaunting a caricature of herself as a self-admitted “functioning alcohol” who obsesses over a married man and fantasizes about killing his wife, all in an uncannily Del Rey-esque inflection. “Hell yeah, I do drugs,” says Swift to her fellow teens, “I do the hardest drug: unrequited love.” Glib as this characterization is, Swift’s dilettantish dabbling in the brand of sentimental salaciousness that Del Rey has honed over her decade-long path from Born To Die’s jeering reception to her current status as pop’s critical darling only reinforces how hackneyed The Tortured Poets Department is in its shallowest moments.

Speaking of “fellow teens,” let’s add Olivio Rodrigo to the conversation. GUTS, one of last year’s best releases, explores a lot of the same themes as The Tortured Poets Department: the messiness of situationships, the rage at how fragile one can feel after a relationship rupture, and how despite the apparent obviousness that we should not be as upset as we are about the “Vampire” or “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived,” that has no practical bearing on our emotions. Comparison between GUTS and The Tortured Poets Department is made even easier by comparing their respective songs “get him back!” and “imgonnagetyouback.” Both relentlessly tread the path of desire like a tightrope, oscillating back and forth between lust and revenge as a motivating force. Rodrigo does so in the playful and reckless tone of a Salt-N-Pepa track, her “consequences be damned” attitude characteristic of the youthful delivery that she excels at. Swift, on the other hand, sounds miserable to be in this position – as she should be! She is fourteen years Rodrigo’s senior and dealing with the same childish love-life bullshit! On “Down Bad,” she calls the irony of her angst for what it is: “teenage petulance.” Her heartbreak simultaneously fuels her self-righteous pain and chastises her for feeling it in the first place as a superstar in her mid-30s. “The Black Dog,” which opens the second half of the album (and would have been a better opener overall for the project than the comparatively superficial “Fortnight”), offers its own tagline for the album as a whole: “old habits die screaming.” For all of its messiness, The Tortured Poets Department’s obsession with pain is not without self-interrogation. It may be more immediately provocative when Swift points the finger at others, like her exes, Kim Kardashian (with an undeniably entertaining homage to Britney Spears’s “If U Seek Amy”), and – perhaps the juiciest of all – the most obsessively entitled of her fans on “But Daddy, I Love Him,” but its most vulnerable moments best indicate what a more successful follow-up to the confessional Midnights could have been.

And yet, despite how apparent this one throughline is across all of The Tortured Poets Department’s inconsistencies, lines like the Grand Theft Auto reference on “So High School” and her reflection on fantasizing about living 1830s America “without all the racists and getting married off for the highest bid” in “I Hate It Here” are treated like smoking guns for Swift being a hack and an antebellum fetishist. To be fair, acting as if “knowing Aristotle” means a damn thing at all is as pretentious as it seems, but if anything, “So High School” is one of Swift’s better attempts at capturing the naivete of adolescent romance and sexuality on a track, and Grand Theft Auto is no less apt of a point of reference for juvenile masculinity as the song’s description of watching American Pie on a Saturday night. And while the 1830s line may be Swift’s most egregious and unnecessary indication of her whiteness sung to date, it is clearly presented as an immature and foolish fantasy serving as an example of how brazenly immature the idea of “being born in the wrong generation” is, particularly when it arises as a reaction to the problems of the present. Even on the album’s peppiest track, “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart,” Swift’s ostensible cheeriness is an audibly forced smile, presented on cue following a four-count to the chorus. Bragging about how “productive” she is despite her pain is the closest thing Swift offers an endorsement of her present state and views, like a flesh-and-bone manifestation of the robotic voice on Radiohead’s “Fitter Happier” flatly describing being “more productive, comfortable, not drinking too much” before admitting to being “a pig in a cage on antibiotics.”

If anything, the bigger problem with The Tortured Poets Department’s self-indulgence is how its unimaginativeness starkly contrasts with its surface level dissimilarities from the rest of the Taylor Swift catalog. For every instance of Swift vocally playing to her strengths on the topic of melodrama, as on elegiac standouts like “So Long, London” and “I Look in People’s Windows,” there are more cases of Swift and her producers playing too close to the hip or disembarking the stream of consciousness before it arrives at a salient point. At too many points, it feels like you have heard this melody on a Taylor Swift song before – or, in the case of “Guilty as Sin?” and “The Alchemist,” far too similar of a vocal chorus melody between two songs on the same album. As great of an “I told you so” song “Cassandra” is, interrupt it at any point with “mad woman” off of folklore, and it feels like you are listening to different parts of the same song like some folk pop version of a prog rock suite that was separated into multiple tracks. Even “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” comes across like a comeback that Swift thought of in the shower during the Reputation era and, frankly, shouldn’t have exited the curtains despite clearing the low bar of sounding sonically fresher than the dated-from-inception material on that album (especially since she already played with the idea of her being a manipulating sociopath far more effectively on Midnights closer “Mastermind”). In a way, the ubiquity of the Era Tour and its conceit hurts The Tortured Poets Department more than it helps, as it primed Swift’s audience – even newcomers like me – to recognize the well-trodden ground in her music. As the 2024 European leg of the tour nears, one wonders how this album’s songs will fit into the “eras” format when in practice, the Tortured Poets Department Era would sound more like an ersatz amalgamation of its predecessors than a distinct “era” of its own.

That is the core paradox of The Tortured Poets Department: it appears to be so obsessed with “Taylor Swift” as an idea in a way that is so appropriate for the present moment of her career, yet that characteristic is also where it draws its flaws from. It is so deeply ingrained in the identity confusion of adolescence that it suffers conceptually from that very issue. There are fragments of a narrative here – that, although it may be more emotionally gratifying to point the finger at some greater force (fate, a conspiracy, society at large, etc.) as the basis for the pain you feel in heartbreak, part of maturity is recognizing the hard truth that sometimes that there is no “good” reason for your heartbreak, just the whims or insecurity of a person you mistakenly placed your trust in – but they are scattered and obscured by too many unfiltered tangents that were only admitted based on their basic connection with the album’s core emotions of regret, rage, and isolation (for example, the trope of “song about California titled ‘California’” was already played out, so what does a vice-laden twist on that idea about Florida have to offer this album?). Despite what its face value pretensions would suggest, The Tortured Poets Department was not meritless in conceit. A lack of focus and reflection is the culprit of its misgivings. In a world where fans clamored for every unreleased song or idea that could be added to their respective albums’ “Taylor’s Version,” Swift may have unwittingly drank her own Kool-Aid and assumed every idea that presented itself in the making of this album would be received with equal excitement, ignoring the principle that when B-sides and demos do not turn out to be hidden gems, they are typically easy to ignore. Album release tracks do not get the same benefit of the doubt.

At the end of the double album’s closing track, “The Manuscript,” Swift muses that when she looks back on the narrative she authored of her past relationship, she feels a dissociation from it (“the story isn’t mine anymore”). The Tortured Poets Department as a whole feels symptomatic of this idea extrapolated to the distance between Taylor Swift, the person who wrote this album, and “Taylor Swift,” the member of the pop music pantheon that the audience perceives – the latter having floated out of reach of the former, as if the idea of Icarus could keep rising upward while his body helplessly grasps upward mid-descent.

★★★

Leave a comment