About eleven months ago, I gradually and unconsciously withdrew from consuming music from a critical lens. A number factors contributed to this including personal loss and large life transitions. While my mental and emotional life eventually returned to a point of relative stability, my captivation with music didn’t follow suit. After a few lost months, the process of scraping my way back to some semblance of “adequate” orientation to the 2023’s music felt like a hopeless endeavor. Keeping up with the times in any respect is inherently a Sisyphian task; the overwhelming speed of life in the streaming era only makes the climb even steeper. The number of weekly new releases exponentially overshadows the amount of time any given person has to listen to music. Most publications account for this by having a staff of writers. I only have myself, and over the past year, I felt paralyzed by my inability and lack of motivation to meet my personal values and goals. As the summer approached, I decided to accept this state of affairs and place my obligations toward this website on hiatus until I felt I could do so in a way that better aligned with the vision I had in mind in Delian Media’s inception.

This approach only addressed half of my internal impediment to writing, however. While I began to listen to new music again toward the end of the year, I didn’t feel an accompanying urge to write more. I found myself in a position where I could write, but one question remained unanswered: why should I write? What is the purpose of spending my time translating my feelings to words in this format? Sure, it provides a personal sense of accomplishment, happiness, and affirmation of identity, but there are other ways I can achieve that. Of my available options, why choose this one? My angst felt larger in scope than its pertinence to my individual experience. Any return to writing necessitated addressing the question: what is the purpose of writing music criticism?

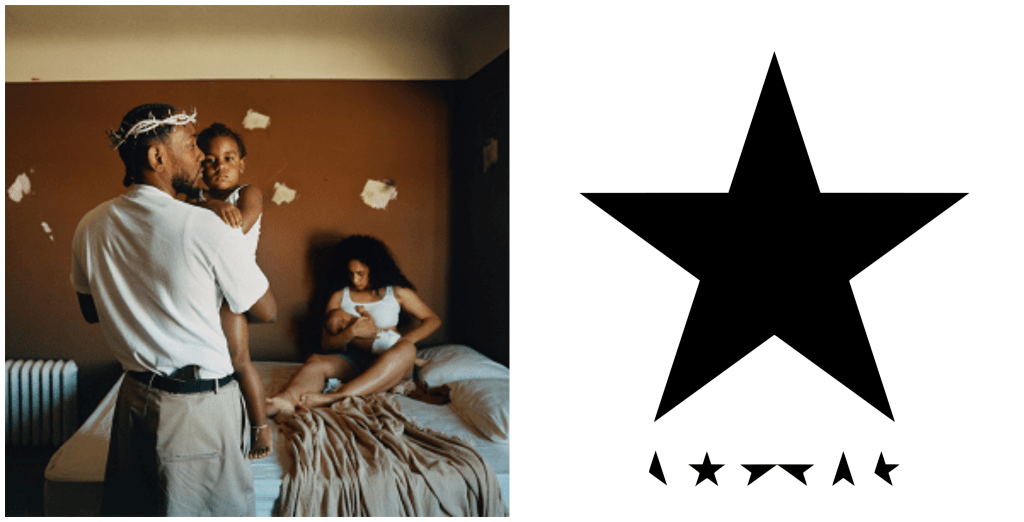

Fittingly, this was a question I had drafted thoughts about when I first seriously considered publishing music criticism. The most natural approach to dipping my toes back in the water seemed to be revisiting those old thoughts, which were contained in an unfinished essay on Kendrick Lamar’s then-new album, Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers. In many ways, Lamar’s discography is what inspired me to think about music critically, but Mr. Morale is what made me question the function of music criticism and its relationship to the function of music itself. While some may interpret the album Lamar reflecting on the consequences of his preceding discography and ending in a space where he feels “above it all” – “it” being a nebulous combination of Lamar’s audience, fanbase, celebrity gossip, and criticism – it doesn’t do so with dismissiveness or pride. Rather, it reaches this conclusion through a humanistic revelation that Lamar will only find the inner peace he seeks by interrogating, accepting, and forgiving himself rather than by seeking validation from others. In both a literal and spiritual sense, Mr. Morale is the denouement of Lamar’s artistic journey with Top Dawg Entertainment. It reminds its listeners that there is a soul underlying the name Kendrick Lamar, that he sees, feels, struggles, and continues reckoning with life just as his listeners do when the needle lifts off the record.

That being said, the pens (or, more accurately, the keyboards) always feel a need to respond. This is the dance between artists and critics. Artists create. Critics analyze, question, hypothesize, and respond. Although many critics and everyday listeners clearly didn’t feel this way, I felt that Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers challenged this arrangement. If someone wears their heart on their sleeve as honestly and vulnerably as Kendrick Lamar does on Mr. Morale, (rightfully) asserts that he is the only person responsible for himself, and concludes that others’ feedback ultimately is secondary to his own self-determination and actions, who are we as music critics to challenge this? Beyond this, all we have left to rightfully criticize is the strictly musical execution of this content, which by comparison can feel frivolous. Personally, there’s nothing more demotivating than feeling like I’m spending my energy on something “frivolous.” Even writing this at this very moment, staring at that word, evokes a sinking feeling in my arms – the body’s natural response to self-examination in the face of doubt.

So, why am I writing this? On one hand, I learn more about myself through writing, through the act of translating ephemeral thoughts and feelings into a concrete, written medium. However, that doesn’t speak to the purpose of making it public. After all, I could write all of this, hide it away in a DOCX file on my computer, and never have it see the light of day, not unlike the infamous vaults of many accomplished musicians like Prince, Bob Dylan, Frank Ocean, or André 3000 (not to suggest that any music critic’s writing is anywhere near as clamored for as the purported hidden gems in these artists’ backlogs). Writing publicly, any public display of creative endeavors, presumes some substantive function of the output, and I don’t believe that my writing is unique in its functional purpose as opposed to other music criticism.

Part of my conception of this purpose of criticism comes from 2022’s Babylon, a film that portrays the rise and fall of the silent film industry in the advent of sound film technology. There is a scene in which Brad Pitt’s character, whose previous success as a silent films star has collapsed into humiliation as an actor fumbling the techniques that sound films demand of their casts, angrily confronts Jean Smart’s character, a movie critic that chronicles the scandalous lives of Hollywood’s biggest stars. She has published a scathing cover story that portrays Pitt’s character as exactly what he is: a washed up has-been who will never achieve the heights of his debaucherous heyday. The fictional public and Babylon’s audience both know this to be true, but the enraged actor rages at the messenger of his plummeting prospects for positive regard. He does so by diminishing the inherent value of her work as a critic, calling her a “cockroach” that peddles nothing more than “gossip.” There is certainly truth to this both in and outside of the film’s context – what is criticism at its core other than feelings and reactions? There isn’t truth to it, so to speak. John Mendelsohn’s infamous panning of Led Zeppelin I for Rolling Stone is but one testament to this fact, not to mention the countless other examples of albums that were more warmly received by the general public long after their original releases. Is “gossip” not an appropriate term for judgmental conjecture?

Babylon’s archetypal critic, however, wears this attack as a badge of honor, a raison d’etre. She compares the film industry to a house in which both humans and cockroaches reside. Much like houses, the occupants of artistic industries are transient in the grand scheme of things, and the house “doesn’t need you any more than it needs the roaches.” The only difference is that the roaches are better fit to survive as they remain “in the dark,” keeping just enough distance to escape the attacks of the humans well-prepared to escape and find another place to call home in case the house burns down. She consoles the actor, though, with the bittersweet reassurance that although creators and commentators are equally temporary in the grand scheme of things, “it’s the idea that sticks.” Both artists’ and critics’ creations have the potential to last far beyond our capacity to survive as individual human beings.

Art’s ability to outlast the moment of its conception also allows for it to be imbued with meaning from two separate sources: that of the artist, and that of the consumer or critic. My favorite album, David Bowie’s Blackstar, epitomizes this process: an artist acutely aware of his last remaining time on this Earth leaves one last reflection on what his final days mean to him in the wake of the monumental artistic career he led up to this moment. David Bowie the human being is gone, but David Bowie the artist is eternal as long as we choose for him to be. Blackstar holds as much meaning as it does because of how it resonates with listeners that continuously regard it in connection to Bowie’s loss and the self-awareness he displayed on the significance of his death to a world that has been irreversibly impacted by his presence and work. Were it not for the meaning-making power of the critic and consumer, art would be just as much of a slave to mortality as its creator. Just as Bowie’s presence in this world is resurrected with every testimonial to the way he influenced someone’s life, art is reconstructed with every unique critical perspective, like a flame stoked with every uniquely shaped branch of kindling placed within its reach.

Perhaps there is inherent vanity in admitting to even the smallest desire for a life that lasts beyond what we are physically allotted – or a part in extending the presence of the people and works we hold dearly – but the only way we can hope to achieve this feat on any level is by earnestly giving it the opportunity to happen through creation. If anything I say or write lasts beyond the moment I press the “submit” button, I know I can’t take sole credit for that occurring. It would be because someone else reads it, takes something out of it, and does whatever they want to do with that. Who am I to stymie that possibility? Who am I to not take part in the sustenance of the art that continues to color my life with meaning? All of our ideas have the potential to be bigger than ourselves. To create is an act of reverence to this fact. Yes, there will be five-star rating scales, ranked lists, and other absurd metrics, but employing these concepts is no less absurd than following the urge to ascribe any significance to what you have to say as a listener. Either way, I’m confident that anyone taking the time to read music criticism knows that it’s what the words and the stars represent, that critic-created meaning, that matters, not the “Metacritic” of it all.

Criticism is a time capsule of our ideas, and this is mine, for you to do whatever you’d like with.

Kendrick Lamar – Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers (2022) ★★★★

Led Zeppelin – Led Zeppelin (1969) ★★★

David Bowie – ★ [Blackstar] (2016) ★★★★★

Leave a comment